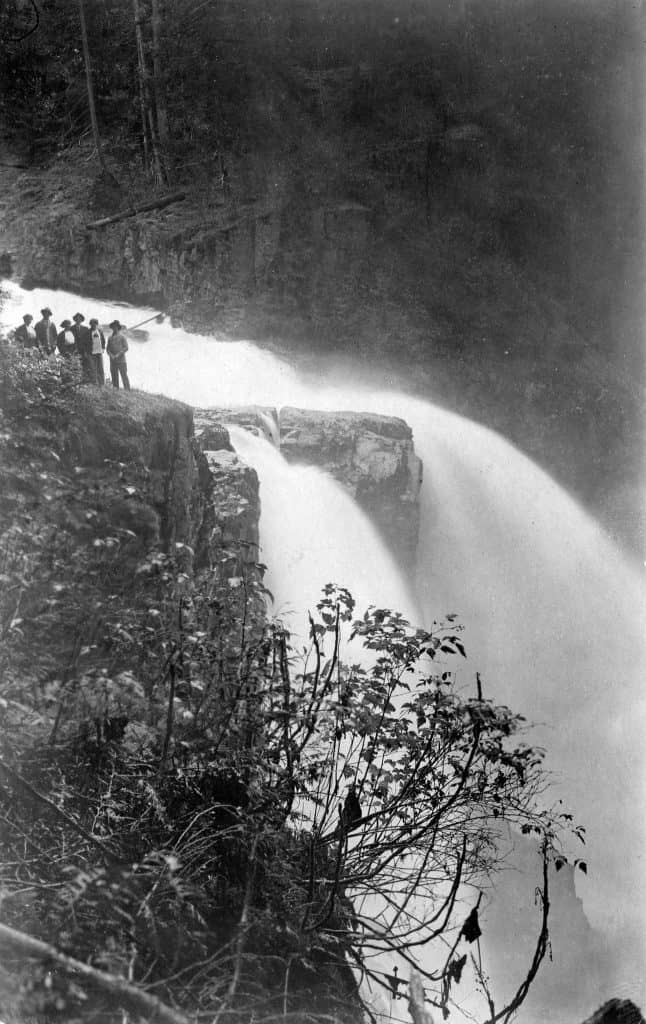

Ever popular for Sunday drives and showing visitors the sights, Elk Falls on the Campbell River has been the highlight of many an excursion over the years. Early residents packed their lunch and spent a leisure day hiking to “The Falls” with their friends. As soon as cars and roads increased, every motorist’s itinerary included this scenic spot. Photographers never tired of recording its turbulence and grandeur.

One autumn day in 1913, a group of young people picnicked at the falls. Among the party were Anna and Elin Thulin, daughters of Charles and Mary Thulin, whose business enterprises laid the foundation for the town of Campbell River. Also in the party was Ethel Barwise, the teacher of 25 pupils in the community’s little schoolhouse on the hill. Fortunately for us, photos of their excursion, now in our archives, have clear identification written on the back in Miss Barwise’s neat, legible script.

The following year, a similar expedition was enthusiastically described by another young woman, Ellen Holm, in her journal. …met at Thulin’s house. Took a picture, and then the party started out…when at the top of the bluff I took a picture of the falls, then journeyed on… (we) turn off the bluff overlooking immediate falls here we take pictures…we have a great time while lunching…all went home with a thorough satisfaction of the day’s journey (diary of Ellen Holm, July 1914).

Those who hiked to the falls traditionally made a stop at the water gauge recorder’s cabin. The Mr. Mason shown in Hetty Barwise’s photo was employed to maintain a daily record of the water flow for the company holding a hydro power license.

When we come to the Gages [sic] house, we all stopped for a drink of water…the bunch scattered. All met again at the Gages cabin. (Ellen Holm, July 1914)

Earlier, in 1910, Harry Johnson was part of a large party which set out to cross the Vancouver Island wilderness from Campbell River to Alberni. They began by going to see “The Falls”, and while some took the recently completed wagon road, Johnson cut through the woods:

…through a seemingly impenetrable mass of huge tree trunks, thickets of alder, crab and dogwood, tangle of devils club, and salmonberry and blackberry, through oozy marshes with giant skunk cabbages, across the Quinsam River on a log, through bracken over our heads, to the mouth of the Campbell canyon. (Journal of Harry McClure Johnson, July 1910)

His guide used a dug-out canoe to take Johnson to a rock on the opposite side of the river, so that he could take a picture directly up the mouth of the canyon. Then they climbed to the top of the canyon wall and followed the water gauger’s trail to the falls.

Johnson, like others, was inspired to poetic superlatives by the falls. He devoted some 600 glowing words to the impressive sight and sound, before continuing his narrative to describe the water gauger’s task. At that time it was Horace Smith who covered a four mile stretch of the river daily to take note of the river height at gauges placed at intervals.

His lone tent stands in the shade of the ever present forest on sloping ground at a bend in the river…In this delightful spot we opened our package of lunch that those in the buckboard had been thoughtful enough to bring along for us.

From the first decades of the 20th century, local citizens were anxious to see the area around the falls preserved as a park. At a meeting of the Courtenay-Comox Board of Trade in 1922, it was reported that “since the road was improved a hundred people had passed over the trail to the Falls in three days, as recorded in a book kept there.” The Board’s Resolutions Committee was charged with drafting a resolution urging preservation of the falls and a strip of timber along the highway. Campbell River’s Board of Trade, incorporated in 1931, took up the cause of asking the government to provide better and facilities for visitors to the falls.

In 1933 Anne Masters, the wife of local farmer Frank Masters, opened a tea house at Elk Falls. For the next five years, Mrs. Masters’ little cedar cabin above the falls welcomed customers from all over the world. Hundreds of people visited Elk Falls every year and enjoyed meals cooled with fresh produce and chicken from the Masters’ farm. The guest book was signed by famous visitors, such as actress Mae West.

To reach the brink of the falls, viewers descended a steep trail and arrived at a ledge which had no protection from the great chasm below. In 1936, a program of the Forestry Branch to alleviate depression-era unemployment set a group of young men to work developing better accessibility at Elk Falls. The “Forestry Training Corps” built a winding path of gradual slope and cleared brush to provide further views.

During the winter of 1936-37, 98 unemployed men lived in tents in two long lines near the “second falls” Moose Falls. Earning 30 cents an hour, paying 75 cents a day for good, square meals, they cleared windfalls, cut trails and made rustic tables and chairs. A concrete platform was built on the outcropping over the falls, and one of the men hand painted directional signs and a picture of the falls for the park entrance. One of the largest of the experimental Forestry Projects Camps for the unemployed, the Elk Falls camp attracted attention across the country: An associated News movie crew was sent from Montreal to document the work.

The following year the camo continued with two objectives: additional park improvements and the beginning of the reforestation program. The reforestation crew planted 60,000 trees in the logged off land adjoining the road to the falls. The most prominent result of the winter’s work, however was a 156-step stairway that zig-zagged its way from the upper viewpoints if the falls. No nails were used in the stairway’s construction: the steps were pinned and dowelled.

These positive achievements were offset by the loss of Mrs. Masters’ “very attractive little tearoom” in 1938. According to the Comox Argus, the government took it over and removed the building.

It is reported that the government has in prospect a lodge, modern and sumptuous. But this year at least there will be no one to take (Mrs. Masters’) place.

The Comox Argus stated in 1939 that there was no beginning yet on a chalet to replace the tearoom, but in 1940 Elk Falls and its neighbouring forest became an officially designated provincial park. A few years later, the long recognized power potential of the mighty falls was at last harnessed in a massive hydro-electric development.

At the beginning of a new century, many visitors of Elk Falls reach it as the early ones did, by foot. A recently completed extension connects a popular trail close to town with the established pathway at the celebrated viewpoint on the Campbell River.

This article first appeared in the Museum’s newsletter, Musings, in May 2001