The Salmon Industry ~ Background

Fishing has provided sustenance to the peoples of coastal British Columbia throughout the ages. With the arrival of Europeans in the 19th century the harvesting of fish, particularly salmon, became an industry as well as a food source.

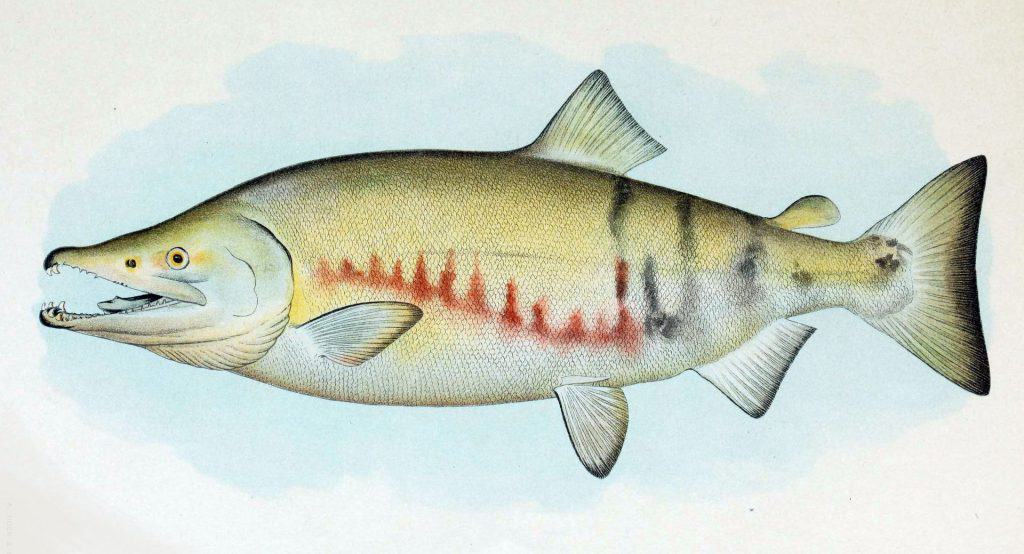

There are five species of salmon

in British Columbia. Their names are given here in English, First Nations’ languages, and Latin…

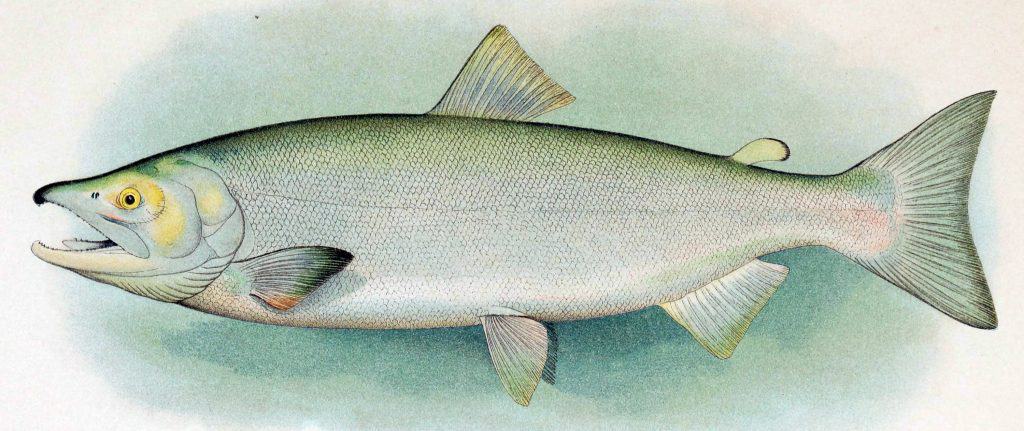

Sockeye

Weight: 5-7 lbs.

- Malik (Kwakwala)

- Miaat (Nuu-chah-nulth)

- tha kai (Mainland Comox)

- Onchorhychus nerka (Latin)

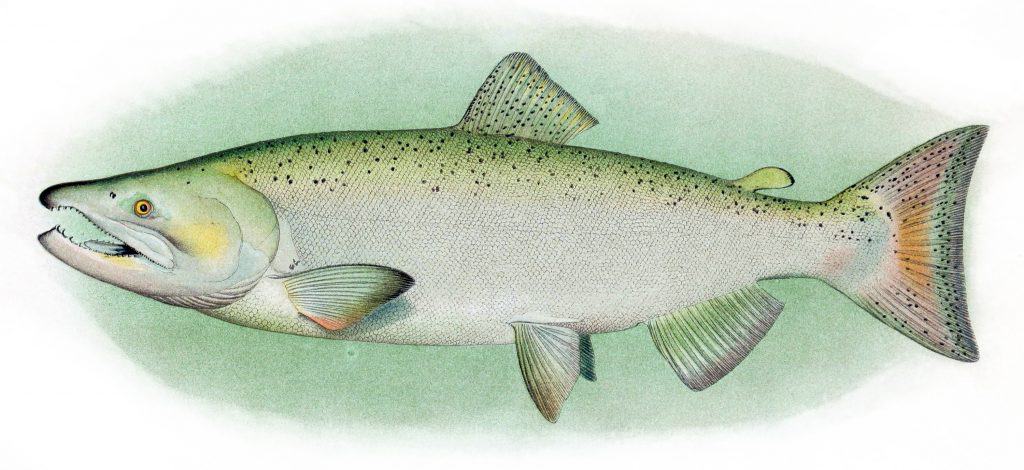

Spring Chinook

Weight: 25-80(+) lbs.

- Tyee, Satsam (Kwakwala)

- Suuha (Nuu-chah-nulth)

- thath m (Mainland Comox)

- Oncorynchus tschawytsch (Latin)

Pink Humpback

Weight: 4-5 lbs.

- Hanu’n (Kwakwala)

- Caapi (Nuu-chah-nulth)

- K watachin (Mainland Comox)

- Oncorhynchus gorbuscha (Latin)

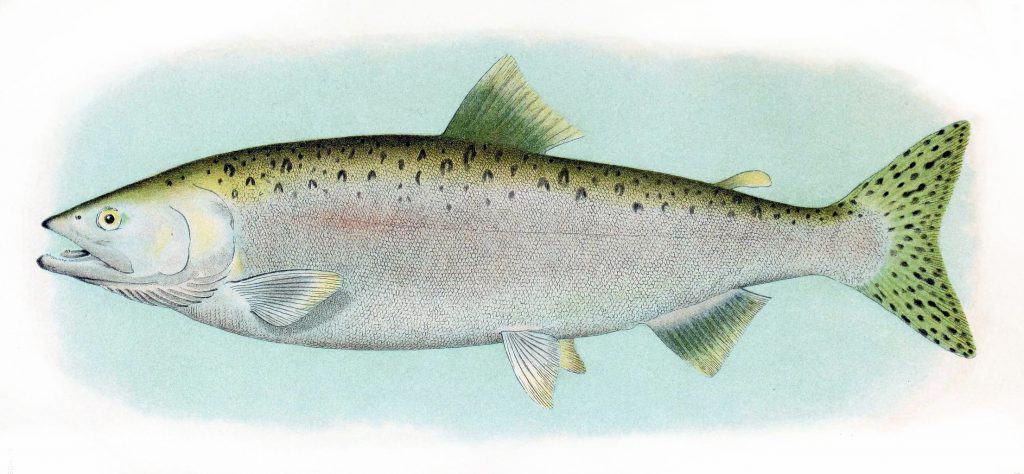

Coho Bluebacks

Weight: 6-12 lbs.

- Dza’wan (Kwakwala)

- Cuw it (Nuu-chah-nulth)

- xaythawk (Mainland Comox)

- Oncorhynchus kisutch (Latin)

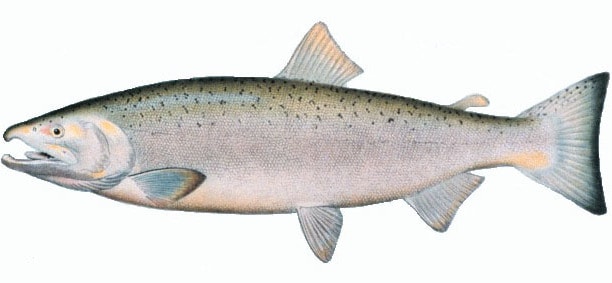

Chum Dog

Weight: 8-10 lbs.

- Gwax’nis (Kwakwala)

- Hink u as (Nuu-chah-nulth)

- tltloxway (Mainland Comox)

- Oncorhynchus keta (Latin)

Gillnetting

The industrial fishery, for the first 30 years, focused on one kind of salmon and one method of catching it. The salmon was sockeye and the method was gillnetting.

A gillnet hangs like an invisible curtain in the water, suspended from a line of floats along its upper edge and weighted along the bottom by a lead line. Salmon swimming into the nets are ensnared by the gills. Salmon can swim around or under the gillnet if they see it. To make them less visible fishermen try to match the net colour to the water.

“If you fished the Fraser River you used a white net, ’cause it’s muddy water… In Rivers Inlet we’d dye it light colours for the colour of the water. We used dark green or black net in the Deepwater Bay area.”

— Jack Souter

“The women made nets durring the winter time. It took them a whole winter to make one gillnet. I used to file needles for my mother. She used Irish linen thread.”

— James Henderson

“We used to use linen nets, years and years ago. That was a lot of work. The bacteria’d get into them and they’d rot. You had to bluestone every week [soak them in copper sulphate]. The tubs were on the floats; every time you come in, just back the boat in, throw the nets into the bluestone tub… This nylon now, there’s not near the work.”

— Rusty Beech

In the early days, fishermen lived and worked six days a week out of open skiffs powered by oars and sometimes a scrap of sail. On Sunday evenings a cannery collector would tow the oar-powered gillnet fleet out to the fishing grounds.

“You threw your net out before the dark set in the evening and went to bed… At daylight you’d start looking around to see where you are and who was your neighbor. You start picking up [your net] and hoping there’s a lot of fish in it.”

— Ole Anderson

“You had your little tent over the front end…We had the primus stoves – before that we just had coal oil cans. We cut the top of them, threaded a few chunks of wire through and burned wood. In light of the morning you would see little bits of smoke coming from every corner. Lots of boats, all the guys making their breakfast.”

— James Henderson

“You went to the cannery office and got a number for your skiff. You went and looked for your skiff number, marked right on the bow. Most of the time it was sunk, tied to a float. You’d bail it out and then you went up to the net loft and presented this number to the net boss. He’d show you the locker where all the floor boards and everything pertaining to that skiff were stashed. You went and packed those down, fitted them in place, put your tent up and you were ready to go.”

— Ole Anderson

Power-driven gillnet drums came into use in the 1940’s. They made the exhausting job of hauling in the net easier, and ten times faster.

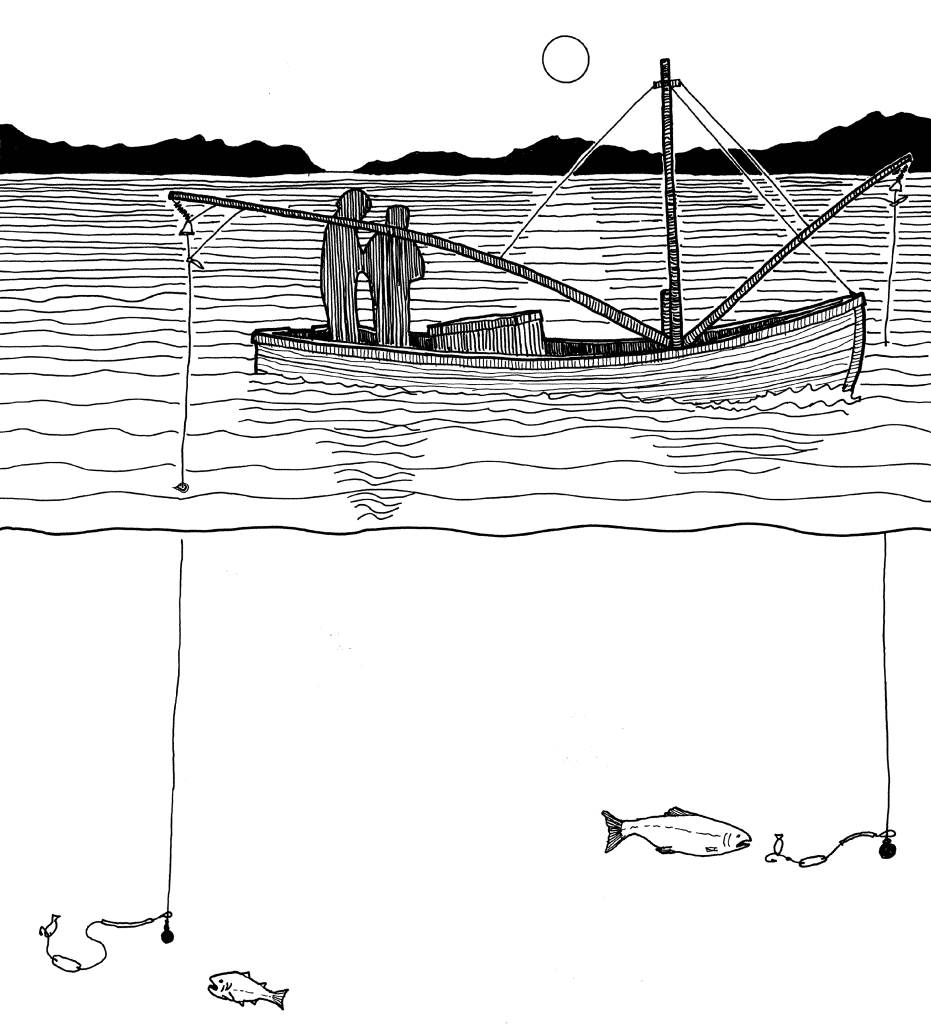

Trolling

Trollers take their fish using a hook and line. Spring and coho, species that rise readily to bait, are the troll fisherman’s primary catch. Adopting methods perfected over the centuries by aboriginal fishermen, early handtrollers used a single line of gear (the end slip knotted around the fisherman’s leg trailed behind an oar-powered skiff or dugout canoe).

“Usually it was all homemade gear. Quite often we’d just use a silver spoon – cut the handle off, drill a hole in it, put a hook on it, catch fish… Didn’t have enough money to buy it new.”

— Tommy Hall

“My mom used to handline with her little rowboat off Butler Point… the flashers were mostly handmade… and if she didn’t have the right bait she would tear a piece of rag, tie it on one and use that for bait.”

— Allen Chickite

Boats used by early hand trollers were as diverse as their owners. They constructed leaky tubs banged together out of a few boards and a can of nails, dugout canoes, and sleek carved hulled double enders. Boats and gear may have changed but the fishing method, well known to the sport fishermen, has not. Trolling is still about coaxing salmon (notoriously fickle) to strike at a baited hook or lure.

“I spent hundreds of hours rowin’ around out there. I used to go out in the morning before daylight, around Copper Bluff, fish the tide there, then I’d row down the Cove… fish there on that tide, then row back and fish Copper Bluff till dark. All day long you’re rowing the whole day… you’d row awhile and you’d bail awhile and you’d fish awhile; and you rowed and you bailed and you fished.”

— Rusty Beech

Trailing behind newly added trolling poles, gear continued to be pulled by hand until gurdies came on the scene in the late 1920s. Simple hand-cranked affairs, they made it possible for trollers to go after fish at deeper depths. The development of spool gurdies that could be powered off a boat motor sped up the whole operation.

“Early in the morning when we used to come out, you could catch big springs right on the surface; just between dark and daylight you could catch big springs right up close you know. An’ then, as it started to get just a little bit lighter, they go deeper and deeper and deeper. That’s why you’ve got the trollers with cannonballs and gurdies and that stuff now, so they can fish all day long.”

— Stan Beech

Hand trolling reached its peak during the Depression years of the 1930s. Between 500 and 700 rowboats plied the waters around the Gulf of Georgia during these lean years, and their mecca was Cape Mudge. Numerous small communities of driftwood shacks clustered on the beaches near this favoured fishing ground.

“All across the face of the Cape out there, there used to be little shacks. And when the camps shut down they’d all come up here and stay in these little shacks and hand troll off the Cape, all summer long.”

— Stan Beech

Seining

Seine gear works by surrounding and confining a school of fish. It is most effective with species like chum and pink which swim in schools near the surface. Sockeye, coho, and spring swim at varied depths and are more difficult to catch with a seine net.

In purse seining a school of fish is completely surrounded with a circular curtain of net. One end of the net is attached to a skiff which holds it in place while the seine boat makes a large circle paying out the rest of the net as it goes. Nets are supported at the top by cork floats and weighted at the bottom by a leadline. At the base of a purseline runs a series of brass rings. Once the school has been surrounded, the purseline is drawn, cinching the net closed.

By the late 1920’s boats had increased in size and power, making comforts like galleys and bunkrooms possible. Powered deck winches helped with the taking up of lines but the backbreaking job of hauling in the net continued to be done by hand. It was a job that could take hours.

The addition of a power driven roller on the seine table aft helped ease the work somewhat, but it was the introduction of the power block and the seine drum in the 1950’s and 60’s that really sped up the process.

“We went to Vancouver right away and had one put on – hydraulic. After we fished a few weeks with this thing it broke down. We could hardly pull the net in. It was just our imagination, I guess. Seines that we pulled by hand all those other years.”

— Sam Hunt

“This fishing game, it’s not like it used to be, no way. The modern style now – they got the big drums. They can throw the net out anyplace and they just rip it in with these big drums.”

— True Krooks

Heavy duty diesel engines now power refrigeration units allowing the fleet to venture further afield, and electronic communication and navigation systems have become standard equipment.

Canneries

For a few short months every year, the quiet inlets and waterways of the central coast used to come alive with bustling communities. Finns from Sointula, Norwegians from Bella Coola, Chinese, Japanese and local First Nations people all converged on the isolated fishing grounds; the canneries hummed with activity.

These cannery operations were not much to look at, just a motley assortment of buildings hunkered down over a forest of pilings, and laced together by narrow boardwalks. At one time there were more than 30 such canneries scattered along the coast between Campbell River and Bella Coola. Bones Bay, Ceepeecee, Wadhams, Tallheo – they are all gone now, but for many years they were part of the ebb and flow of coastal life.

“When the first cannery men came to this coast, they put up canneries at the places where our people were living – at the best salmon rivers… The cannery managers needed the Indian men to bring in the fish and the women to work in the canneries. It was good… Later when other people got into the fishing business, we had to fight for our place in it.”

— Harry Assu

In the early years of the industry the entire canning operation was done by hand – from making and filling the cans to gluing on the labels. In a young province with a sparse population it was workers, not fish, that were in short supply.

With the labour shortages came the demand for better wages. Mechanization provided cannery owners with a solution. Fully automated canning lines were in place by 1913, although many cannery owners, like Anderson at the Quathiaski cannery, chose to continue hand packing because it commanded a higher price.

Gang knives cut the fish into can-sized segments. This was one of the earliest steps to be mechanized in the canning process.

Quathiaski Cannery on Quadra Island (directly across from Campbell River) was built in 1904. Prior to then most canneries on the central coast were situated near highly productive sockeye runs and supplied by a fleet of gillnetters. The Quathiaski Cannery processed the less marketable species and was supplied by a local troll fishery as well as drag seines.

When motorized seiners were just coming into their own, the owner of Quathiaski Cannery was quick to recognize their potential. The fleet of Quathiaski seiners was among the earliest on this part of the coast.

The number of canneries along the B.C. coast steadily diminished as the stocks decreased and high speed packer boats and on-board refrigeration reduced the need to process salmon close to the fishing grounds.