Since the 1880’s logging has played an important role in the development of this region. The area north of Powell River, stretching up to Drury Inlet on the north shore of Queen Charlotte Sound, known by loggers as the “Jungles” is a complex maze of islands, inlets and channels.

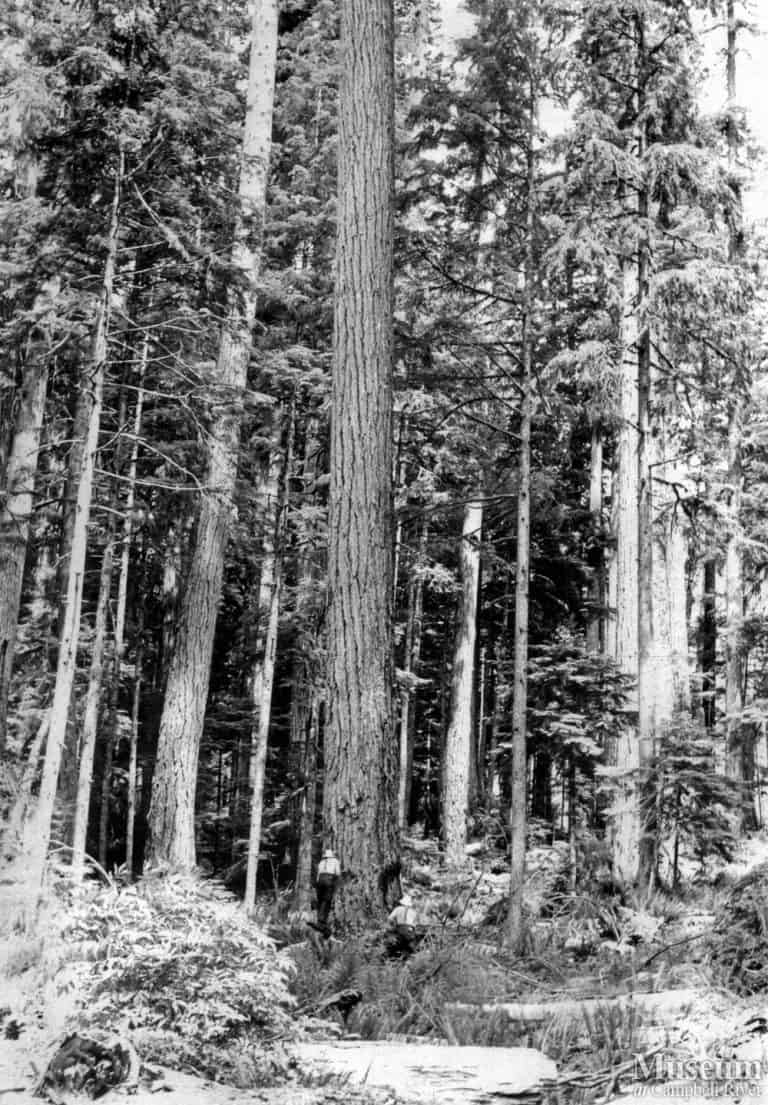

Unlike the massive stands of huge timber found in other regions, this rugged shoreline with its network of waterways was littered with pockets of fir trees. Tenaciously growing on steep inclines many of these trees could be felled directly into the water with minimal equipment.

The accessibility enabled a myriad of small-scale individual enterprises with limited capital to flourish in this region. The “Jungles” more than any other region on the BC coast is known as the birthplace of the independent logger.

Logging has evolved from these early days as methods of falling and hauling have been influenced greatly by technology.

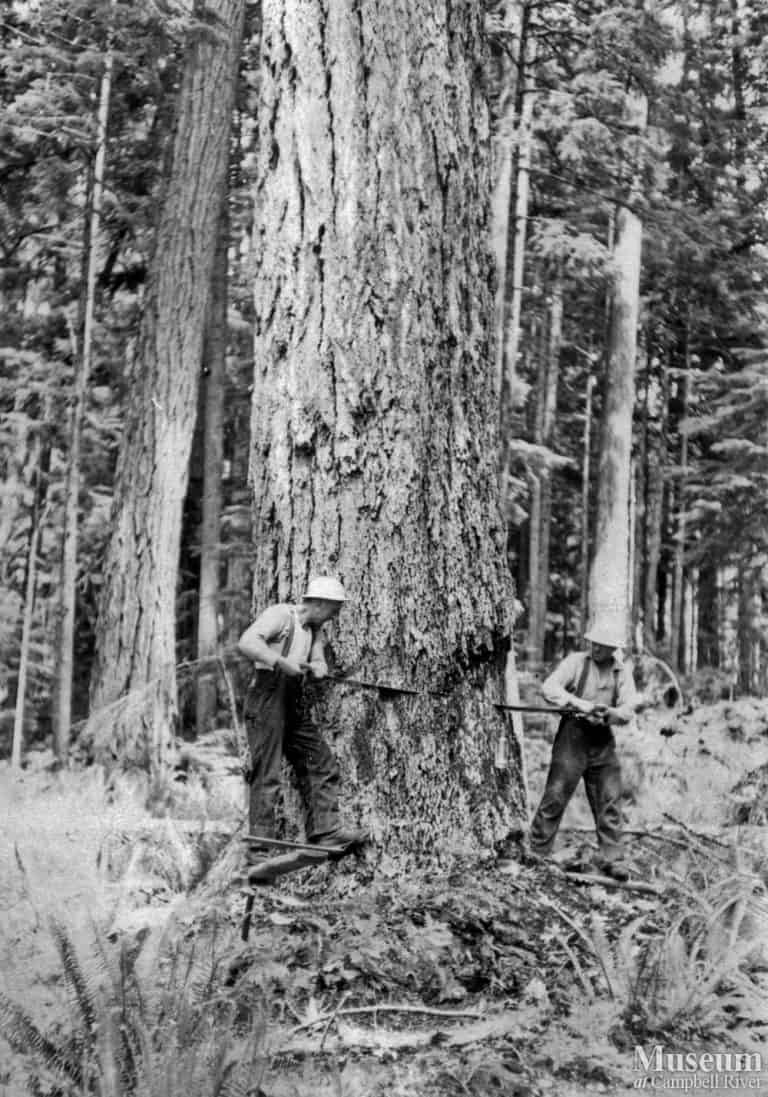

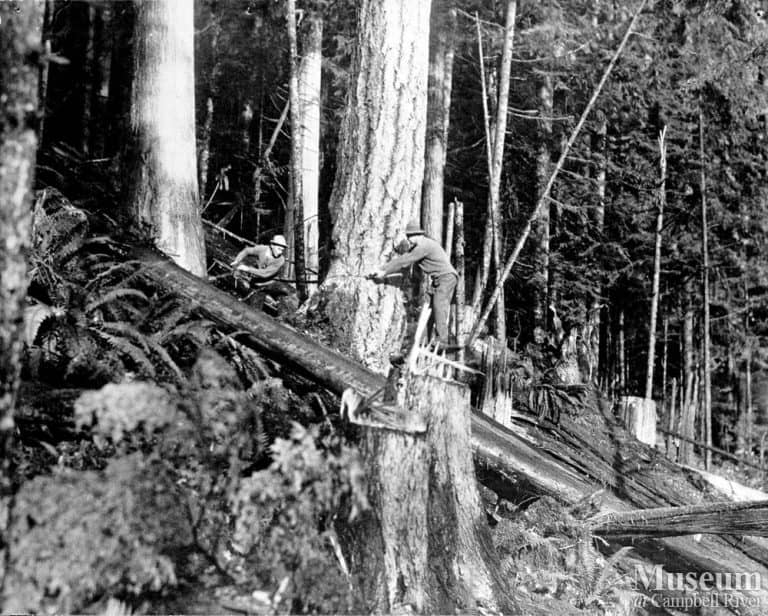

Crosscut Falling

Equipped with axes, crosscut saws, a pair of springboards, an oil bottle and a sack of wedges, early loggers were faced with the formidable task of falling a seemingly endless forest. They worked in groups of three known as a “set.” Falling was not only hard work but demanded a high degree of skill to accurately estimate the direction in which the tree would fall.

After carefully assessing the lean of the tree and the surrounding terrain the fallers would chop an undercut in the tree using razor sharp double-bitted axes.

Then, perched atop the springboards positioned above the flare of the tree, the two fallers would rhythmically pull the crosscut saw back and forth until the tree fell. “Timber!” they would holler as the tree came crashing to the ground.

It was then the job of the bucker to remove the branches and cut the tree into lengths in readiness for yarding, or in some cases rolling, sliding or just plain cajoling the log down the hillside to the water.

Watching a pair of skilled hand fallers at work was a sight worth seeing. With sharp caulked boots gripping the narrow springboards they swung their razor-sharp double-bitted axes with a rhythm that was almost mechanical.

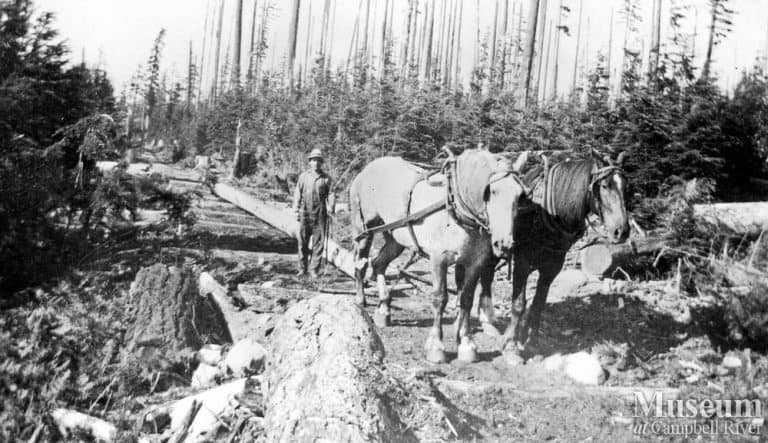

Hauling

Once a tree had been felled, there still remained the awesome task of transporting it to a sawmill. At first, only shoreline timber was selected and then simply floated to its destination. However, as suitable foreshore stands became depleted, a means of moving inland timber to the water had to be devised.

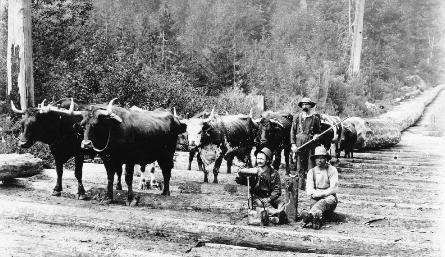

Hauling Teams of oxen, often as many as 14 yolked together, were called into service. Hauling 4 or 5 logs at a time over greased skid roads, the oxen muscled the timber down to the beach. This method of log transportation was a great advantage to early loggers, but was quickly replaced by more efficient methods. Oxen were very strong but also very slow and (as the saying goes…) stubborn!

In order to transport the logs to the water, the oxen needed to be coaxed and encouraged by the bullpuncher. Accompanying the bullpuncher in this effort were the pigman, who was responsible for chaining the logs together and the skidgreaser, who had the smelly task of greasing the skid roads!

“The oxen you know, was a peculiar animal – he had no speed in him. He would just plod along. He had his plodding gait and that was all. All the cursing and swearing and goading with the goad stick made no difference. He would let a bellow out of him and still he rolled one shoulder to the other.”

— Charles H. Grant

Orchard interview)

Oxen were soon replaced by horses, who were both smarter and faster. Then the horses fell victim to technology as the steam engine was now the workhorse of the logging industry.

As the demand for lumber soared, efforts to speed up the transportation of logs through mechanization spelled an end to animal powered logging.

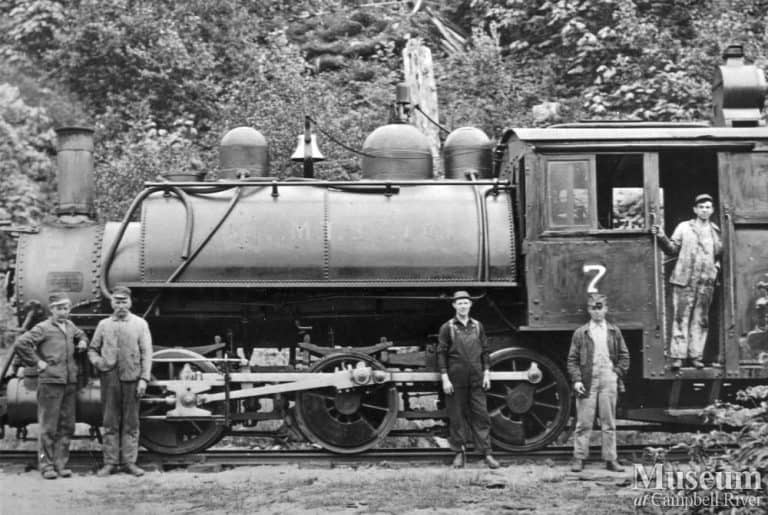

The need for an efficient means of transportation resulted in a wide range of logging equipment designed and manufactured specifically for use on the coast. The era of steam had arrived with the introduction of the steam donkey and the locomotive to coastal logging.

Steam DonkeyDonkey loading and yarding unit. The steam donkey replaced horses and oxen with the power of steam. The donkeys were able to yard logs faster, cheaper and more reliable than any animal. Loggers were now able to reach logs away from the coast that would have been impossible to skid with oxen or horses.

Use of a spar tree, along with the steam donkeys and locomotives, allowed timber companies to harvest in larger, more remote areas than ever before. This was accomplished using high lead and skyline systems to yard the timber and load them onto the rail cars. The spar tree was a branchless tree that was rigged with a network of cables, pulleys and carriages that were powered by the steam donkey. Together this team could effectively yard logs by lifting them from thier resting place and then lowering them onto the rail cars.

The logs would then be transported by rails to a nearby inlet or river where they would be dumped for sorting. Unlike the leisurely pace of working with animals, these new systems demanded a faster more intensive work pace requiring a skilled crew who worked as a strong unit.

As a result of this new technology, during the 1920’s large scale locomotive logging operations flourished throughout the B.C. coast and rail lines were popping up everywhere. Railroad logging demanded a high level of investment as well as increased maintenance and operational costs. A number of large companies soon joined the logging scene which had formerly been dominated by small producers.

Logging now moved farther into the hills as logging camps were created using the power of the locomotive. These camps were usually made up of several bunkhouses, a shop, a cookhouse and a Mess Hall, that were transported to the site on rails. For those who worked in the woods this change marked a gradual end to a transient lifestyle, as the camps became unique communities.

Locally camps such as ERT Camp “Quinsam” and Bloedel, Stewart & Welch’s “Bloedel” provided a stable home for the logger and his family.

“There was about 500 men in the camp, in Menzie’s Bay at that time. And I never seen that many men in one place. And, boy you stand there by the cookhouse I remember many times – the cook had the door locked, bolted on the inside, because the guys were pushing on the doors, wanting to get in… they were hungry.

“Finally I got into the stream going in there, you know. ‘Cause the cook or one of the flunkies comes out and they ring the bell, the triangle… dingala – dingala – dingala – ding – ding… Boy-oh-boy, everybody heard that, you know; they just rushed for the cookhouse door. You’d get out of the way, (or) you’d get run over.”

— Ture Krooks,

recalling Menzie’s Bay beach camp 1925

Although large scale operations flourished, the small producer continued to play an important role in the coastal logging scene. Though often unable to scrape together enough capital to establish railway shows, the small producer was quick to recognize the potential of the early motor trucks to haul logs. Although the cost of constructing roads could be high, purchasing and operating trucks was much less than the costly locomotives.

The future of logging had arrived with the introduction of the logging truck.

Truck HaulingThe first logging trucks were a rough affair, often a conglomeration of parts held together with a hope and a prayer. They were small, primitive and underpowered compared to the giants of today, but they proved their worth immediately as a economical alternative to railway logging.

With their hard rubber tires, they ran on wooden plank roads known as fore-and-aft roads which were constructed of hand-hewn timbers laid on crossties. A guard rail on the inside or outside of the hewn road insured the truck did not veer off track. On steep inclines rip-rap, a length of cable or rod bent in a zig-zag pattern and spiked to the deck with staples, provided much needed traction for the trucks.

These early trucks were becoming a common sight in the woods of the coast during the boom of the 1920’s.

The jig was actually up for the big locie shows with the appearance of the first logging trucks with their open cabs and hard rubber tires… trucks could go where trains couldn’t and chase the timber into the hills when the flat country ran out.

“They could negotiate grades that no locie without a snub line on it could ever hope to attempt… trucks were simply a faster and more practical method of hauling wood.”

— Peter Trower,

From the Hill to the Spill

Although trucks provided a cheaper method of hauling, locomotive logging continued to dominate the scene during the war years due to the unavailability of new equipment. As a result the logging industry entered the post war years with a pent-up need for faster and better machines and methods. This soon came with such innovations as diesel engines, trailers and pneumatic tires that were strong enough to carry the heavy loads.

Eventually these trucks were everywhere and road replaced rails, as the logging truck was proving to be far more economical and practical than the locomotive. This change also allowed the independent logger to once again become a factor on the coast. Armed with trucks and chainsaws, the modern logger was born and was here to stay. Soon the large locomotive camps were dismantled and the logger and his family could move into town.

The logging truck continues to play an important role in the economic development of this region. Although there have been and will continue to be technological advancements, what remains constant is the unique physical environment of this coast and the strength and ingenuity of the men and women involved in this integral industry.